Benefit And One Barrier To Implementing Evidence-based Practice Change?

- Systematic review

- Open up Access

- Published:

Barriers and facilitators to implementing bear witness-based guidelines in long-term care: a qualitative evidence synthesis

Implementation Scientific discipline volume 16, Article number:lxx (2021) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

The long-term care setting poses unique challenges and opportunities for effective cognition translation. The objectives of this review are to (1) synthesize barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based guidelines in long-term care, as defined as a domicile where residents crave 24-h nursing intendance, and 50% of the population is over the age of 65 years; and (ii) map barriers and facilitators to the Behaviour Change Bike framework to inform theory-guided knowledge translation strategies.

Methods

Following the guidance of the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group Guidance Series and the ENTREQ reporting guidelines, we systematically reviewed the reported experiences of long-term intendance staff on implementing testify-based guidelines into do. MEDLINE Pubmed, EMBASE Ovid, and CINAHL were searched from the earliest date available until May 2021. 2 contained reviewers selected primary studies for inclusion if they were conducted in long-term care and reported the perspective or experiences of long-term care staff with implementing an testify-based do guideline about health conditions. Appraisal of the included studies was conducted using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklist and confidence in the findings with the Grade-CERQual approach.

Findings

Afterwards screening 2680 abstracts, we retrieved 115 full-text articles; 33 of these articles met the inclusion criteria. Barriers included time constraints and inadequate staffing, toll and lack of resources, and lack of teamwork and organizational support. Facilitators included leadership and champions, well-designed strategies, protocols, and resource, and adequate services, resource, and fourth dimension. The about frequent Behaviour Change Wheel components were concrete and social opportunity and psychological capability. We concluded moderate or high confidence in all but one of our review findings.

Conclusions

Hereafter knowledge translation strategies to implement guidelines in long-term care should target concrete and social opportunity and psychological capability, and include interventions such equally environmental restructuring, training, and education.

Background

Description of the topic

Show-based guidelines summarize the all-time available research on wellness care practices to enhance the provision of consequent and appropriate care [i]. However, bringing bear witness into clinical practice is an ongoing challenge. Systematic reviews on guideline adherence and utilization found that a large percent of bachelor guidelines do not accept sustained implementation where appropriate [2, 3]. For case, an organization may implement a new guideline into practice, but the behaviours associated with it do non continue later initial introduction. In dissimilarity, if new show emerges, suggesting electric current practices are not constructive, they must be de-adopted. Guideline implementation into routine healthcare can be unpredictable, and trial-and-error approaches take been costly and ineffective, producing variable results of guideline broadcasting and implementation [four, 5]. Consequently, there has been increasing interest in employing theories, models, and frameworks to direct guideline implementation. Noesis translation focuses on developing ways to efficiently and effectively interpret evidence-based cognition into clinical intendance. Theory-based guideline implementation is desirable every bit it ensures the implementation plan and processes consider circuitous factors that influence success of guideline uptake prior to implementation. In this fashion, implementers navigate around potential pitfalls to successful implementation by conscientiously bookkeeping for previously identified factors which could hinder their success.

Many existing cognition translation frameworks guide researchers to consider complex factors that influence the success of guideline uptake prior to the implementation procedure [six,vii,8]. The Behaviour Change Bicycle is ane framework that prompts users to select noesis translation interventions based on physical, social, psychological, and environmental factors that influence the capability, opportunity, and motivation needed for behaviour change (COM-B) [7]. Central to the Behaviour Change Bicycle, the COM-B system incorporates Capability, Opportunity, and 1000otivation equally sources of Behaviour. Users can determine what needs to change for the desired behaviour (east.chiliad., guideline implementation) to occur by identifying barriers and facilitators and mapping them onto the COM-B organization. The Behaviour Change Bicycle so guides users to select potential knowledge translation interventions based on their COM-B analysis [vii]. Therefore, by studying barriers and facilitators in a context-specific surround, interventions tin be designed in a theory-informed manner which increases the potential for sustainable exercise change.

Why is it important to do this review?

The need to effectively translate evidence-based guidelines into practice is especially pressing for older adults [9] as the proportion of the population anile 65 years and over is growing exponentially [10]. Older adults with complex needs and comorbidities oftentimes live in long-term care (LTC) homes, which are living spaces for adults who have meaning health challenges to receive access to 24-h nursing and personal care [11]. Guidelines accept been adult for various health conditions in LTC homes ranging from diabetes to force per unit area ulcer prevention [12]. However, near knowledge translation studies on guideline implementation for older adults practise not include LTC homes [13]. Knowledge translation strategies from other settings are poorly transferable to LTC considering of the skill mix of the staff, surround, complication of the residents' conditions, and availability of resources [fourteen]. Cognition translation strategies must be specifically designed for LTC given the unique context of wellness care provision in this setting. While barriers and facilitators to guideline implementation have been systematically reviewed in other healthcare settings [13, 15], no such analyses have been conducted for the LTC sector.

How this review might inform what is already known in this area

The findings of our study will synthesize barriers and facilitators to prove-based guideline implementation across health conditions in LTC and mapped onto the COM-B components. Our identified barriers and facilitators and suggested knowledge translation strategies based on the COM-B mapping can exist used to design theory-guided noesis translation interventions in LTC. This will save time, attempt, and resource in identifying barriers and facilitators so that planners can blueprint interventions more quickly and efficiently. Further, our review volition identify gaps in inquiry related to show-based guideline implementation in LTC and make suggestions for future work.

Objectives

The objectives of this qualitative evidence synthesis are to (1) synthesize barriers and facilitators that LTC staff experience during the implementation of testify-based guidelines and (two) map the identified barriers and facilitators to the central component of the Behaviour Change Wheel framework to inform future theory-guided cognition translation intervention development in the LTC setting. Our research question is "What are the barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based health care guidelines in LTC homes from the perspectives of staff (eastward.g., nurses, wellness care aides, physicians)?" The phenomena of interest is implementation of health care guidelines into do and the factors that hinder or facilitate implementation. The context is LTC homes who provide 24-h nursing care for mostly frail, medically complex older adults across the world in the 21st century.

Methods

Nosotros conducted a qualitative evidence synthesis following the guidance of the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Grouping Guidance Serial [16] and the ENTREQ reporting guidelines (Checklist can be found in Additional file 1) [17].

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included main studies that employ qualitative study designs such as ethnography, phenomenology, case studies, grounded theory studies, and qualitative process evaluations. Nosotros included studies that use both qualitative methods for data collection (eastward.g., focus group discussions, individual interviews, ascertainment, diaries, certificate analysis, open-concluded survey questions) and qualitative methods for data analysis (e.k., thematic assay, framework assay, grounded theory). We included studies that collect information using qualitative methods just practice not analyse these data using qualitative assay methods (e.1000., open-concluded survey questions where the response data are analysed using descriptive statistics only) as long every bit the results or findings place barriers and facilitators as described below. Nosotros only included published studies written in English. We did not exclude studies based on our assessment of methodological limitations. We used this information nearly methodological limitations to assess our confidence in the review findings.

Target behaviour

The target behaviour was implementing prove-based guidelines into practice (e.g., pressure injury management, pain, fractures, deprescribing). Barriers were divers equally any factors that obstruct the chapters for LTC staff and homes to implement guidelines, while facilitators were whatever factors that enable implementation.

Participants

The grouping required to perform the target behaviour was LTC staff which included personal back up workers, clinicians (due east.1000., nurses, physicians, pharmacists, dieticians, physiotherapists), and dwelling administration (e.g., directors of care).

Setting

Studies were included if they were conducted in LTC, defined equally a dwelling house where residents require 24-h nursing intendance, and fifty% of the population is over the historic period of 65 years.

Search methods for identification of studies

Relevant articles were identified through a pre-planned literature search in MEDLINE Pubmed (1946 to nowadays), EMBASE Ovid (1974 to present), and CINAHL (1981 to nowadays) in July 2019 and updated in 2021. The key concepts used in the searches were "long-term intendance", "guidelines", "implementation", "barriers", and "facilitators". The fundamental concepts were combined with the Boolean operator AND, and the search words within each concept were combined with OR. The full search strategy can be plant in Additional file two.

Selection of studies

All titles and abstracts were screened past two squad members (CM and YB) using a pilot-tested form and were included if they met our inclusion criteria as described above. Nosotros excluded articles that were non written in English, reported on implementation of guidelines that were not show-based (i.e., the article did not demonstrate that the guideline was developed through systematic review of literature), clinical commentaries, editorials, legal cases, letters, newspaper articles, abstracts, or unpublished literature. After title and abstract screening, the total texts of relevant articles were screened independently past the same two reviewers using a airplane pilot-tested class. Disagreements were arbitrated past a 3rd party.

Data extraction

Two team members (CM and YB) independently extracted and charted the following data in duplicate using a airplane pilot-tested data extraction form: report description (title, author, country, province/land/region, blueprint, objectives, data drove methods, data analysis methods, name of guidelines examined, health topic of guideline examined, behaviour change framework, model, or theory used), private participant description (profession(south), number, mean age, sexual activity, sampling technique, response rate), LTC habitation description (number, size, buying, rurality), and results/findings (identified barriers and facilitators). Data for the study results were extracted verbatim from the text under the heading "results" or "findings" where authors identified barriers and facilitators (or a synonym, e.thou., challenges or supports for change) to implementation of the guidelines examined.

Assessing the methodological limitations of included studies

The validity, robustness, and applicability of each included study was appraised by ii team members (CM and PH) independently and in duplicate using the Disquisitional Appraisement Skills Programme (CASP) Checklist [18]. Consensus between the two reviewers was required, and any discrepancies were adjudicated by a 3rd political party. No studies were weighted or excluded based on the appraisal results.

Data management, analysis, and synthesis

Our synthesis follows the 3-stage Thomas and Harden approach to inductive thematic synthesis [nineteen]. We completed two steps of this procedure, as our master aim was to produce descriptive themes of barriers and facilitators to guideline implementation across different wellness guidelines to so map on the COM-B components. Later extracting the reported barriers and facilitators, 2 team members (CM and YB) created a codebook that was grouped into recurrent themes (e.1000., resource, staffing issues). The two team members so independently and in duplicate coded each extracted barrier and facilitator with the themes from the code book. If new codes emerged, they were added iteratively to the code book and the barriers and facilitators were re-themed accordingly. The frequency of the themes was tallied equally the number of times the theme was mentioned across the included manufactures. Finally, the themes were mapped onto the COM-B components of the Behaviour Change Wheel by the two team members independently and in duplicate. Based on a synthesis of 19 previously published behaviour change frameworks, the Behaviour Modify Wheel provides tables that link the central COM-B components to potential knowledge translation intervention functions based on their expected effectiveness in relation to the barriers and facilitators. For example, if physical opportunity is a barrier, and so training, restriction, environmental restructuring, and enablement are potential intervention functions. Potential knowledge translation intervention functions were listed with their associated barriers and facilitators and COM-B components. Whatsoever discrepancies between the ii members were resolved by a third party. All data analysis and synthesis were performed in Microsoft Excel. Table 1 provide definitions for the COM-B components and knowledge translation intervention functions equally outlined by the Behaviour Change Bike.

Assessing our confidence in the review findings

Two review authors (CM and PH) assessed the level of confidence for each finding using the GRADE-CERQual [20]. Grade-CERQual assesses confidence in the evidence based on four key components: methodological limitations of included studies, coherence of the review findings, adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding, and relevance of the included studies to the review question. Later on assessing each of the iv components, we fabricated a judgement about the overall confidence in the testify supporting the review finding and report it as loftier, moderate, depression, or very depression. The final assessment was based on consensus among the 2 review authors. All findings started as high confidence and were graded downward if there were important concerns regarding any of the GRADE-CERQual components.

Summary of qualitative findings table and evidence profile

We nowadays summaries of the findings and our assessments of confidence in these findings in the Summary of qualitative findings table (Table 3). We nowadays detailed descriptions of our confidence cess in an Evidence Contour (Additional file 3).

Review author reflexivity

The authors of this article are a multidisciplinary group of researchers and clinicians focused on geriatrics and improving care provision in LTC. They accept engaged in several enquiry studies in LTC including assessment of barriers and facilitators to implementation of practices, evolution of guidelines, cognition translation, and randomized controlled trials. Since we have prior experience assessing barriers and facilitators in the LTC setting, some biases may exist as we may have preconceived ideas of what barriers and facilitators exist. Included studies that were conducted past ane of the authors of the current newspaper were analyzed by two team members who were not authors of the included studies.

Findings

Results of the search

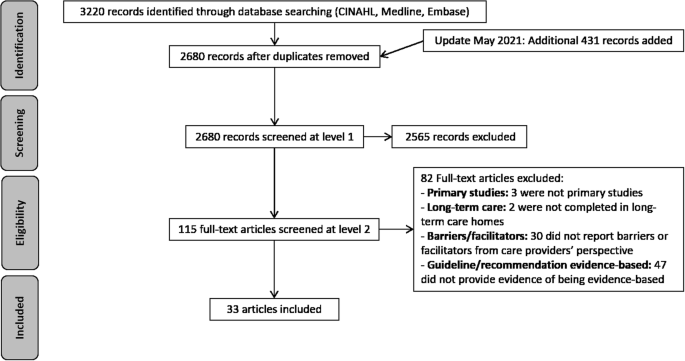

After screening 2680 articles, 33 that were published between 2004 and 2020 were included in the analyses (Fig. 1).

Menstruation of articles through the study

Description of the studies

Most studies were conducted in Canada and Australia, with much fewer in holland, the USA, England, Sweden, Deutschland, South Korea, and Kingdom of belgium (Table 2). A wide range of guidelines were examined, with the most frequent being oral wellness, medication reviews, and pain protocols. A diversity of written report designs were employed including qualitative studies, mixed method, multiple case studies, and process evaluations. Focus groups, interviews, and document analysis were the most frequent information collection methods, and thematic or content assay was used to clarify data for 73% of included studies. But vi studies used a behaviour change framework, model, or theory to guide their work which included the framework adult past Greenhalgh et al. (Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation), Organizational Readiness for Alter, Theoretical Domains Framework, Organization Learning Theory, Promoting Action in on Enquiry Implementation in Health Services, and Normalization Process Theory.

Included studies recruited 12 to 500 LTC home staff from a variety of professions including nursing, medicine, direction, rehabilitation (e.g., physical and occupational therapy), chemist's shop, and nutrient services (Table 3). Many studies did not report the age or sex of their participants. For those that did, the hateful historic period of included staff ranged from 38 to 54 years, and the percent of participants who were female ranged from 46% to 100%. Convenience and purposeful sampling were the almost common methods of recruitment. At the LTC home level, the number of homes included ranged from ii to 120, and the number of residents per home ranged from xl to 251; though many studies did not written report these values (eleven% did non written report number of homes, 46% did not report number of residents per home). Similarly, more than than half (58%) of the included studies did not written report the ownership or rurality of the included homes.

Methodological limitations of the studies

Most studies had a clear research aim which was appropriately addressed through a qualitative research pattern. Likewise, most studies employed appropriate recruitment strategies and information were collected in a fashion that addressed the research question. In some studies, the clarification of data analysis techniques was limited. Overall, nosotros found poor reporting of enquiry reflexivity across near of the included studies. Details of the assessments of methodological limitations for individual studies are institute in Additional file iv.

Confidence in the review findings

We had moderate or high conviction in all but one of our review findings. Confidence was most often downgraded due to concerns with methodological limitations including a lack of word about brownie of qualitative findings and a lack of reflexivity. The information was almost always relevant as almost studies examined our phenomena and population of interest. The total CERQual evidence contour tin can exist found in Additional file 3.

Review findings

The line-past-line thematic assay of barriers and facilitators is plant in Additional file v. Tabular array iv provides a summary of the identified barrier and facilitator themes, their definitions and frequency, the articles contributing to the theme, and the CERQual cess and explanation of confidence in the findings. The nigh frequently identified barriers and facilitators were consistent beyond guideline topics, while others were more specific to the content of the guideline. For instance, near all articles identified fourth dimension constraints and inadequate staffing (high conviction), and price and lack of resources (high confidence) equally barriers. Nevertheless, guideline impracticality (high confidence) and taking a reactive approach (moderate confidence) were just identified in articles that discussed concrete activity, influenza immunization, pneumonia treatment, and heart failure. In some instances, barriers and facilitators were opposites of each other, with barriers being actual and facilitators being perceived. For instance, if time and money were an identified barrier, the staff perceived they could more hands implement the guideline with more than time and resource (facilitator). However, some facilitators were also bodily. For case, champions to promote implementation of the guidelines within the home was an bodily facilitator in several manufactures.

Physical and social opportunity were the COM-B components that the identified barriers and facilitators mapped onto well-nigh frequently (Tabular array 5). Inside physical and social opportunity, time constraints and inadequate staffing (high confidence), cost and lack of resource (high confidence), and lack of teamwork (loftier confidence) and organizational support (high confidence) were frequently reported barriers, while leadership and champions (high confidence), well designed strategies, protocols, and resources (high conviction), and adequate services, resource and fourth dimension (high confidence) were frequent facilitators. Training, restriction, ecology restructuring, modelling, and enablement are noesis translation intervention functions suggested by the Behaviour Change Wheel to overcome barriers associated with physical and social opportunity. The COM-B component of psychological capability represented knowledge gaps (high confidence) equally a barrier and adequate knowledge and education (high conviction) equally a facilitator. Instruction, preparation, environmental restructuring, modeling, and enablement are knowledge translation intervention functions suggested by the Behaviour Change Wheel to overcome barriers associated with psychological capability. Finally, reflective and automatic motivation had barriers relating to conflict with clinical autonomy (loftier conviction), behavior against the guideline (loftier confidence), moral distress (moderate confidence), reluctance to alter (high confidence), emotional responses to work and confidence in skills (moderate confidence), and alter fatigue (moderate confidence). Facilitators with respect to reflective and automated motivation were having noticeable outcomes occur from guidelines implementation (moderate confidence), a sense of conviction that the guidelines are testify-based and will demonstrate comeback (low confidence), and a positive emotional response to piece of work and the intervention (high confidence). The Behaviour Change Bicycle suggests training, pedagogy, persuasion, modelling, enablement, incentivization, coercion, and environmental restructuring equally potential noesis translation interventions to overcome automated and reflective motivation.

Review author reflexivity

We previously described our initial positioning earlier (see review author reflexivity in a higher place). Throughout the review, our positioning remained the aforementioned. During analysis and writing of the discussion, we felt our findings confirmed our initial ideas about the near frequent barriers and facilitators.

Discussions

Summary of the main findings

We systematically identified barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based guidelines in LTC and used behaviour alter theory to link them to candidate knowledge translation functions. Across several guideline topics, fourth dimension constraints and inadequate staffing, cost and lack of resources, noesis gaps, and lack of teamwork and organizational support were frequently identified barriers. In contrast, leadership and champions, well-designed strategies, protocols, and resources, and adequate services, resource and fourth dimension were often identified equally facilitators. Linking to the central components of the Behaviour Change Wheel suggests physical and social opportunities and psychological capability are mutual targets for alter to overcome barriers and leverage facilitators. While the near oft identified barriers and facilitators appear to be universal regardless of guideline topics (eastward.thou., hurting, mood, concrete action, heart failure), some guidelines may have nuanced deportment that have unique barriers and facilitators. We suggest that future cognition translation and implementation scientific discipline researchers assume the most often identified barriers and facilitators in our review are nowadays and that they design strategies targeted at physical and social opportunity and psychological capability. A farther assay of barriers and facilitators may be necessary if the actions outlined by the guideline accept unique features that could create boosted barriers and facilitators.

The reported barriers and facilitators in our qualitative systematic review most oft mapped onto the cardinal Behaviour Modify Wheel components physical and social opportunity: the opportunities afforded by the environment (east.g., time, resources, locations, cues, physical affordances) and interpersonal influences (e.g., social cues and cultural norms that influence the style we think about things). The findings that environmental opportunities (e.thou., irresolute the social and physical context of care provision) are significant barriers to implementing evidence-based guidelines repeat recent concerns surrounding quality of care provided in LTC highlighted past the COVID-19 pandemic [21] and is consistent with previous literature. Indeed, there have been recurrent reports of lack of funding and subsequent personnel shortages leading to decreased time to provide services to increasingly complex residents in LTC [22, 23]. Limited teamwork has also previously been identified equally a barrier in LTC [24]. Linkage inside the Behaviour Modify Cycle suggests that training, restriction, environmental restructuring, enablement, and modelling are candidate knowledge translation intervention functions to overcome the identified barriers and leverage the facilitators.

Given the recent international interest in improving LTC during and after the COVID-nineteen pandemic and the subsequent impetus to support significant changes to the sector [21, 25], several of the Behaviour Alter Cycle identified intervention functions could be feasible. For example, ecology restructuring involves changing the physical or social context to support guideline implementation. Resident-centred care approaches restructure the environment of intendance provision around the resident and address several of the barriers and facilitators identified in our review. For instance, one such testify-based approach, Neighbourhood Squad Development, focuses on modifying the physical LTC environment, reorganizing delivery of care services, and adjustment team members (due east.g., LTC staff, family unit, residents) to collaborate in providing care [26]. Several of the studies included in our review as well identified involving residents and family members as a facilitator of implementing evidence-based guidelines, supporting a resident-centred care approach.

Knowledge gaps pertaining to the information within guidelines, change fatigue, and lack of interest in work were frequently identified barriers and facilitators in our systematic review, which mapped onto the COM-B domains of psychological capability and cogitating and automatic motivation. In many countries, most direct care within LTC homes is provided past care aides (east.1000., personal support workers, wellness care aides, standing intendance assistants, resident assistants) [27, 28] who often have the lowest level of instruction, receive the lowest fiscal compensation, have the least autonomy, and feel work-related exhaustion and poor job satisfaction [27, 29]. Cognition gaps as well apply to other members of the LTC interprofessional teams including licensed nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and rehabilitation and recreation and leisure providers. Indeed, several of the studies included in our review revealed cognition gaps for dissimilar members of the LTC team. Education and training are potential cognition translation intervention functions to overcome barriers associated with psychological capability and cogitating and automatic motivation. Grooming for care aides is variable within and between countries. For example, in Canada, there are currently no national educational activity standards for care aides working in LTC, and training varies widely between provinces [30]. Training of other members of the interprofessional team (e.m., physicians, physical therapists) oft does not include a focus on geriatrics or LTC, nor is it standardized. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed a major gap in standardized training for all team members most proper personal protective equipment employ and conservation [31]. Consistent didactics and preparation with monitored national standards for all LTC staff may be ane targeted knowledge translation strategy. However, for continuing education to exist effective in LTC, information technology must be supported by the organization, and ongoing expert back up is needed to enable and reinforce learning [32] which further bolsters the argument for a team-based, resident-centred approach.

Comparison with other reviews and implications for the field

This is the offset study to synthesize barriers and facilitators to guideline implementation in LTC from the perspectives of staff across healthcare conditions. Barriers and facilitators to guideline implementation accept been systematically reviewed in other healthcare settings, merely until at present, no syntheses have been developed for the LTC context. Farther, we not but identified the barriers and facilitators but besides mapped them onto the cardinal constructs of the Behaviour Change Bicycle. This helps us explore the reasons why the factors identified are barriers and facilitators and the findings can be used to inform the development of future theory-guided knowledge translation intervention development.

Overall abyss and applicability of the testify

From a methodological betoken of view, the studies included in our review had several limitations. First, studies often did not report important information most the LTC dwelling house(s) which provides context from which the results were derived, such as the size, ownership, and rurality of the LTC home. The context of the LTC domicile including number of residents in a home, funding structure, and access to resources has been previously shown to touch implementation of best practice guidelines in LTC [14]. Future authors of LTC research are encouraged to fully draw the setting so that readers tin adequately assess the generalizability of the results to their context, or reasons why they may experience different outcomes. Further, authors should include a fulsome description of the context including intendance philosophy of the home, staffing levels, and health arrangement influences (east.g., public or private funding). Second, near authors did non critically examine their own role, potential bias, and influence during assay and presentation of results. Reflexivity, or the acknowledgement of underlying behavior and values held by researcher in selecting and justifying their methodological approach [33], is essential in assessing the authenticity of qualitative results [34]. Authors of qualitative enquiry are encouraged to include a reflexive statement when reporting their results that describes their role in data collection, analysis and interpretation, and potential resulting biases that may arise.

Limitations of the review

A strength of our study is that nosotros synthesized information across different health conditions within the LTC sector. Given that there are probable many similarities among barriers and facilitators across guidelines for different atmospheric condition in the LTC setting, the findings of this qualitative evidence synthesis can help inform the implementation of whatsoever evidence-based guideline in LTC homes. Even so, a limitation of our report is that we did not assess the strength of the barriers and facilitators identified in this review. A frequently identified barrier may not hinder implementation as much as ane that is less frequently reported. We argue that frequently reported barriers beyond several guideline topics are withal important to identify as they can inform pattern of noesis translation strategies regardless of topic. Future work should examine the strength of barriers and facilitators in LTC for implementing evidence-based guidelines and determine which barriers significantly limit implementation to add to our piece of work. Another limitation is that we did not complete the third stage of the Thomas and Harden arroyo to thematic synthesis [xix] to develop analytical themes that enable the development of new theoretical insights and findings not seen at private primary report level. However, we saw mapping the barriers and facilitator themes onto the COM-B components as a style to accept our assay to the adjacent footstep and provide recommendations for theory-guided knowledge translation strategies and empathise why barriers and facilitators may exist. Additionally, equally per the Thomas and Harden approach, we did not code directly onto whatsoever part of the manuscripts and focused our extraction on the results and findings sections, meaning key evidence may have been missed. We only included studies published in English language which limits the generalizability of our findings to English-speaking countries or those that can pay for translation services. There is subjectivity in mapping of barriers and facilitators onto the COM-B components; some barriers and facilitators could map onto different components depending on the readers' interpretations. Though we identified candidate intervention functions for implementing guidelines in LTC, nosotros did not assess which ones are feasible and realistic to implement. Our adjacent steps are to apply the APEASE criteria [35] in consultation with stakeholders to determine the near appropriate intervention functions for the LTC sector.

Conclusion and implications

Implications for exercise

We suggest that people designing LTC interventions to support guideline implementation assume the most frequently identified barriers (time constraints and inadequate staffing, price and lack of resource, knowledge gaps, and lack of teamwork and organizational back up) and facilitators (leadership and champions, well-designed strategies, protocols, and resources, and acceptable services, resources and time) in our review are present and blueprint strategies targeted at physical and social opportunity and psychological adequacy. Further assay of barriers and facilitators specific to the guideline they are implementing may be necessary if the deportment outlined by the guideline accept unique features that could cause additional barriers and facilitators.

Implications for research

Implications for research have been developed based on the findings of our study and our Class-CERQual assessment of findings. Time to come qualitative piece of work in this area should transparently written report researcher reflexivity including a reflection of the researchers' roles and the influence this may have on the findings of the study. Additionally, researchers must fully describe the context of their LTC setting to ensure readers can determine whether the findings apply to their local LTC context. A full description of context would include the care philosophy of the abode, staffing levels, and health system influences (due east.m., public or individual funding) amidst other factors.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- COM-B:

-

Capabilitiy, opportunity, motivation, behaviour

- LTC:

-

Long-term care

References

-

Davidoff F, Case K, Fried Pw. Bear witness-based medicine: why all the fuss? Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(9):727.

-

Bauer MS. A review of quantitative studies of adherence to mental health clinical practice guidelines. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10(three):138–53.

-

Mickan South, Burls A, Glasziou P. Patterns of "leakage" in the utilisation of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1032):670–ix.

-

Eccles 1000, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston Grand, Pitts N. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(two):107–12.

-

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline broadcasting and implementation strategies. Health Technol Appraise. 2004;viii(half-dozen):i-72.

-

Helfrich CD, Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ, Daggett GS, Sahay A, Ritchie G, et al. A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting activity on research implementation in wellness services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):82.

-

Michie Due south, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour modify wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour modify interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(ane):42.

-

Wilson KM, Brady TJ, Lesesne C, NCCDPHP Piece of work Group on Translation. An organizing framework for translation in public health: the noesis to activity framework - PubMed. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(ii):A46.

-

Ellen ME, Panisset U, Araujo de Carvalho I, Goodwin J, Beard J. A Knowledge Translation framework on ageing and health. Wellness Policy. 2017;121(3):282–291.

-

U.S. Section of Wellness and Homo Services. Why population aging matters - a global perspective. National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health; 2017.

-

World Wellness Organization. The Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. 2020. Bachelor from: https://world wide web.who.int/ageing/global-strategy/en/

-

Registered Nurses' Clan of Ontario. Clinical BPGs. Long-term care best practices toolkit, 2nd edition. Available from: https://ltctoolkit.rnao.ca/clinical-topics/bpgs. [cited 2020 Mar 23]

-

Bostrom A-M, Slaughter SE, Chojecki D, Estabrooks CA. What do we know almost cognition translation in the care of older adults? A scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):210–nine.

-

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Hayduk L, Morgan D, Cummings GG, Ginsburg L, et al. The influence of organizational context on best practice use past intendance aides in residential long-term care settings. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(vi):537.e1–537.e10.

-

Francke AL, Smit MC, De Veer AJE, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health intendance professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:38.

-

Noyes J, Berth A, Cargo M, Flemming One thousand, Garside R, Hannes M, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 1: introduction. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:35–eight.

-

Tong A, Flemming One thousand, McInnes Due east, Oliver Due south, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative enquiry: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181.

-

CASP. Qualitative appraisal checklist for qualitative research. Critical Appraisal Skills Program. 2011. Available from: https://casp-uk.cyberspace/casp-tools-checklists/. [cited 2020 May 28]

-

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative inquiry in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

-

Lewin South, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying Class-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13(Suppl i):2.

-

Grabowski DC, Mor 5. Nursing abode care in crisis in the wake of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(1):23–iv.

-

Castle NG, Engberg J. Staff turnover and quality of care in nursing homes. Med Intendance. 2005;43(half-dozen):616–26.

-

Ng R, Lane North, Tanuseputro P, Mojaverian N, Talarico R, Wodchis WP, et al. Increasing complexity of new nursing home residents in Ontario, Canada: a series cross-sectional study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020.

-

Kane R, Due west J. Information technology shouldn't exist this way: the failure of long-term intendance. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005.

-

Gordon A, Goodman C, Achterberg W, Barker RO, Burns E, Hanratty B, et al. Commentary: COVID in care homes-challenges and dilemmas in healthcare delivery - PubMed. Historic period Ageing. 2020;thirteen:afaa113.

-

Boscart VM, Sidani S, Ploeg J, Dupuis SL, Heckman G, Kim JL, et al. Neighbourhood Team Development to promote resident centred approaches in nursing homes: a protocol for a multi component intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):922.

-

Andersen Eastward. Working in long-term residential care: a qualitative meta summary encompassing roles, working environments, work satisfaction, and factors affecting recruitment and retention of nurse aides. Glob J Wellness Sci. 2009;i(ii):2.

-

Berta W, Ginsburg Fifty, Gilbart Due east, Lemieux-Charles 50, Davis D. What, why, and how intendance protocols are implemented in Ontario nursing homes. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. 2013;32(1):73–85.

-

Caspar S, Ratner PA, Phinney A, MacKinnon K. The influence of organizational systems on information exchange in long-term care facilities. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(7):951–65.

-

Association of Canadian Community Colleges. Canadian educational standards for personal intendance providers. 2012.

-

Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons Chiliad, James A, Taylor J, Spicer K, et al. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-COV-2 infections in residents of a long-term intendance skilled nursing facility - King County, Washington, March 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(xiii):377–81.

-

Stolee P, Esbaugh J, Aylward S, Cathers T, Harvey DP, Hillier LM, et al. Factors associated with the effectiveness of continuing education in long-term care. Gerontologist. 2005;45(three):399–409.

-

Shacklock G, Smyth J. Being reflexive in critical educational and social enquiry. London: Falmer; 1998.

-

Reid AM, Brown JM, Smith JM, Cope Air-conditioning, Jamieson S. Ethical dilemmas and reflexivity in qualitative inquiry. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(two):69–75.

-

Michie S West R. AL. The Behaviour Modify Wheel: a guide to designing interventions. Silverback Publishing; 2014.

-

Phipps E, Watson C, Mearkle R, Lock S. Influenza in carehome residents: applying a conceptual framework to describe barriers to the implementation of guidance on treatment and prophylaxis. J Public Wellness Oxf Engl. 2020;43(three):602–nine.

-

Abraham J, Kupfer R, Behncke A, Berger-Hoger B, Icks A, Haastert B, et al. Implementation of a multicomponent intervention to prevent physical restraints in nursing homes (IMPRINT): a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;96:27–34.

-

Villarosa AR, Clark S, Villarosa AC, Patterson Norrie T, Macdonald South, Anlezark J, et al. Promoting oral wellness care amidst people living in residential anile care facilities: perceptions of care staff. Gerodontology. 2018;35(iii):177–84.

-

Huhtinen Eastward, Quinn E, Hess I, Najjar Z, Gupta Fifty. Understanding barriers to effective management of influenza outbreaks by residential aged care facilities. Australas J Ageing. 2019;38(i):60–3.

-

Nilsen P, Wallerstedt B, Behm 50, Ahlstrom Grand. Towards evidence-based palliative intendance in nursing homes in Sweden: a qualitative study informed by the organizational readiness to alter theory. Implement Sci IS. 2018;13(1):ane.

-

DuBeau CE, Ouslander JG, Palmer MH. Noesis and attitudes of nursing home staff and surveyors most the revised federal guidance for incontinence intendance. Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):468–79.

-

Birney A, Charland P, Cole Yard. Evaluation of the antipsychotic medication review process at four long-term facilities in Alberta. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;nine:499–509.

-

Fallon T, Buikstra E, Cameron One thousand, Hegney D, Mackenzie D, March J, et al. Implementation of oral health recommendations into 2 residential aged care facilities in a regional Australian city. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2006;4(3):162–79.

-

Baert 5, Gorus E, Calleeuw K, De Capitalist Due west, Bautmans I. An administrator'due south perspective on the organization of concrete activity for older adults in long-term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(ane):75–84.

-

Alamri SH, Kennedy CC, Marr S, Lohfeld L, Skidmore CJ, Papaioannou A. Strategies to overcome barriers to implementing osteoporosis and fracture prevention guidelines in long-term care: a qualitative assay of action plans suggested past front line staff in Ontario, Canada. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:94.

-

Kaasalainen Due south, Ploeg J, Donald F, Coker Due east, Brazil M, Martin-Misener R, et al. Positioning clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners as change champions to implement a hurting protocol in long-term care. Pain Manag Nurs Off J Am Soc Hurting Manag Nurses. 2015;16(two):78–88.

-

Vikstrom S, Sandman P-O, Stenwall E, Bostrom A-M, Saarnio Fifty, Kindblom K, et al. A model for implementing guidelines for person-centered care in a nursing home setting. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(i):49–59.

-

Strachan PH, Kaasalainen S, Horton A, Jarman H, D'Elia T, Van Der Horst M-L, et al. Managing heart failure in the long-term care setting: nurses' experiences in Ontario, Canada. Nurs Res. 2014;63(five):357–65.

-

Lim CJ, Kwong M, Stuart RL, Buising KL, Friedman ND, Bennett N, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship in residential aged care facilities: need and readiness assessment. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:410.

-

Dellefield ME, Magnabosco JL. Pressure ulcer prevention in nursing homes: nurse descriptions of private and organization level factors. Geriatr Nurs N Y Northward. 2014;35(two):97–104.

-

Bamford C, Heaven B, May C, Moynihan P. Implementing nutrition guidelines for older people in residential care homes: a qualitative study using Normalization Process Theory. Implement Sci IS. 2012;7:106.

-

Kaasalainen S, Brazil Thou, Akhtar-Danesh N, Coker Due east, Ploeg J, Donald F, et al. The evaluation of an interdisciplinary hurting protocol in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):664.e1-8.

-

Verkaik R, Francke AL, van Meijel B, Ouwerkerk J, Ribbe MW, Bensing JM. Introducing a nursing guideline on depression in dementia: a multiple case report on influencing factors. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(9):1129–39.

-

Berta Westward, Teare GF, Gilbart E, Ginsburg LS, Lemieux-Charles 50, Davis D, et al. Spanning the know-do gap: agreement knowledge awarding and capacity in long-term care homes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(9):1326–34.

-

McConigley R, Toye C, Goucke R, Kristjanson LJ. Developing recommendations for implementing the Australian Hurting Guild's pain direction strategies in residential anile intendance. Australas J Ageing. 2008;27(one):45–9.

-

Cheek J, Gilbert A, Ballantyne A, Penhall R. Factors influencing the implementation of quality use of medicines in residential anile intendance. Drugs Crumbling. 2004;21(12):813–24.

-

Hilton S, Sheppard JJ, Hemsley B. Feasibility of implementing oral wellness guidelines in residential care settings: views of nursing staff and residential intendance workers. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:194–203.

-

Lau D, Banaszak-Holl J, Nigam A. Perception and use of guidelines and interprofessional dynamics: assessing their roles in guideline adherence in delivering medications in nursing homes. Qual Manag Health Intendance. 2007;16(2):135–45.

-

Buss I, Halfens R, Abu-Saad H, Kok Grand. Pressure ulcer prevention in nursing homes: views and beliefs of enrolled nurses and other health care workers. J Clin Nurs Wiley-Blackwell. 2004;13(six):668–76.

-

Maaden T, Steen JT, Koopmans RTCM, Doncker SMMM, Anema JR, Hertogh CMPM, et al. Symptom relief in patients with pneumonia and dementia: implementation of a practise guideline. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(8):829–39.

-

Kong East-H, Kim H, Kim H. Nursing dwelling house staff's perceptions of barriers and needs in implementing person-centred care for people living with dementia: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2021;23. Epub ahead of impress

-

Jeong E, Park J, Chang SO. Development and evaluation of clinical do guideline for delirium in long-term care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8255.

-

Eldh AC, Rycroft-Malone J, van der Zijpp T, McMullan C, Hawkes C. Using nonparticipant observation as a method to empathize implementation context in show-based do. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2020;17(3):185–92.

-

Cossette B, Bruneau M-A, Couturier Y, Gilbert Due south, Boyer D, Ricard J, et al. Optimizing Practices, Use, Care and Services-Antipsychotics (OPUS-AP) in long-term intendance centers in Québec, Canada: a strategy for best practices. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(two):212–9.

-

Surr CA, Holloway I, Walwyn RE, Griffiths AW, Meads D, Kelley R, et al. Dementia Intendance MappingTM to reduce agitation in care domicile residents with dementia: the Epic cluster RCT. Health Technol Assess Winch Engl. 2020;24(16):ane–172.

-

Desveaux L, Halko R, Marani H, Feldman S, Ivers NM. Importance of team functioning equally a target of quality improvement initiatives in nursing homes: a qualitative process evaluation. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2019;39(1):21–eight.

-

Walker P, Kifley A, Kurrle South, Cameron ID. Procedure outcomes of a multifaceted, interdisciplinary knowledge translation intervention in aged care: results from the vitamin D implementation (ViDAus) written report. BMC Geriatr. 2019;xix(one):177.

Acknowledgements

When preparing this protocol/review, we used EPOC'south Protocol and Review Template for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis (Glenton C, Bohren MA, Downe S, Paulsen EJ, Lewin South, on behalf of Effective Practice and Organisation of Intendance (EPOC). EPOC Qualitative Evidence Synthesis: Protocol and review template. Version 1.1. EPOC Resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Public Wellness; 2020), available at: http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors).

Funding

CM was supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. YB was supported by a summertime studentship from the McMaster Establish for Research on Aging. The funder had no role in the study, estimation of data, or decision to submit results.

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

CM conceptualized the study; CM and YB conducted information assay; CM, YB, and PH interpreted the findings; and CM and YB wrote the manuscript. LG, SS, and AP provided content expertise and assisted with interpretation of the findings. The authors critically read, contributed to, and canonical the manuscript for submission.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicative.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, every bit long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third political party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If textile is non included in the article's Creative Eatables licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted apply, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/ane.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the information.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McArthur, C., Bai, Y., Hewston, P. et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing prove-based guidelines in long-term care: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Implementation Sci 16, seventy (2021). https://doi.org/x.1186/s13012-021-01140-0

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s13012-021-01140-0

Keywords

- Long-term care

- Barriers

- Facilitators

- Evidence-based

- Guidelines

- Knowledge translation

Source: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-021-01140-0

Posted by: stubbslieuphe.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Benefit And One Barrier To Implementing Evidence-based Practice Change?"

Post a Comment